When Jeff Bezos returned to Earth after a trip to the edge of space, there were sighs of relief — and it's likely some of them were from board members of the $1.8 trillion company he started 27 years ago.

For Amazon's founder and executive chairman, the trip on Tuesday aboard a rocket from his venture Blue Origin may have been the realization of a childhood dream.

But for corporate boards, any time a top executive does something dangerous, it ends up posing a major risk to the the company's bottom line.

Yet as more executives continue to push the envelope, boards recognize there isn't much they can do.

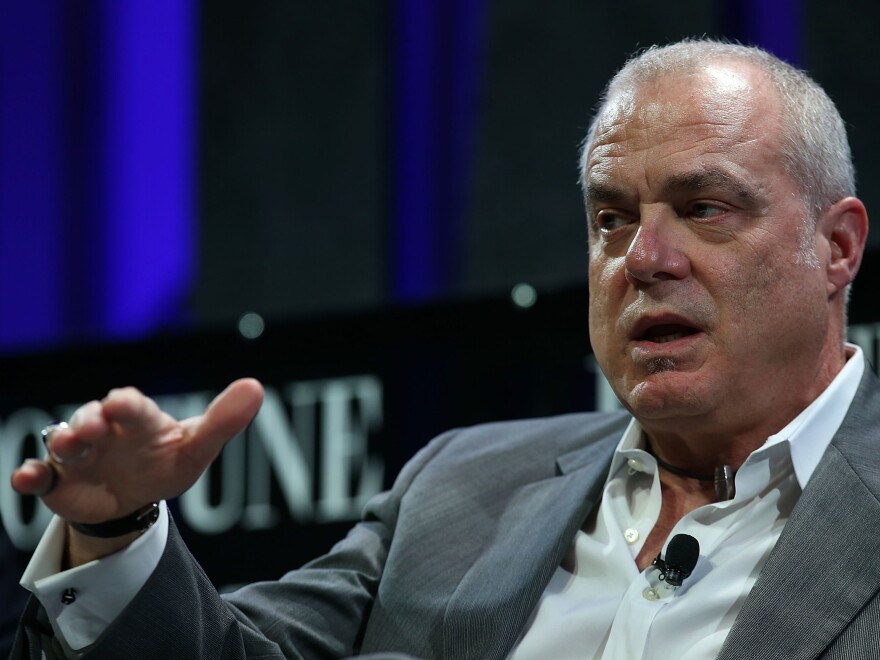

Take Mark Bertolini, the former chairman and CEO of health insurance company Aetna.

A person with a self-described "adrenaline drive," Bertolini got his first dirt bike when he was 8 years old, and today, he owns three Harley-Davidson motorcycles and a Ducati. Bertolini also loves downhill skiing.

That was certainly a worry for Aetna's board.

"When I was first named CEO and chairman and was asked to look at a contract, they had skiing and motorcycling in there as exclusions," Bertolini remembers. "I told them that wouldn't work for me."

Aetna's board had good reason to try to hold Bertolini back. Just a few years before he was named CEO in 2010, Bertolini had been skiing in Vermont. He looked over his shoulder to check something; he hit a tree and dived headfirst into a river.

Bertolini spent two hours in the icy water, with five broken vertebrae, and ended up in coma.

Yet even in the middle of a long, difficult recovery, Bertolini, who was then a top executive, told Aetna's board he didn't intend to stop skiing or riding motorcycles.

"I said that, 'You know, I would continue to be careful and take the appropriate precautions,' " he says. "But my life was my life, and I wasn't willing to give those up."

Zuckerberg grooves to music on his hydrofoil surfboard

Bertolini is not alone in his push for thrills.

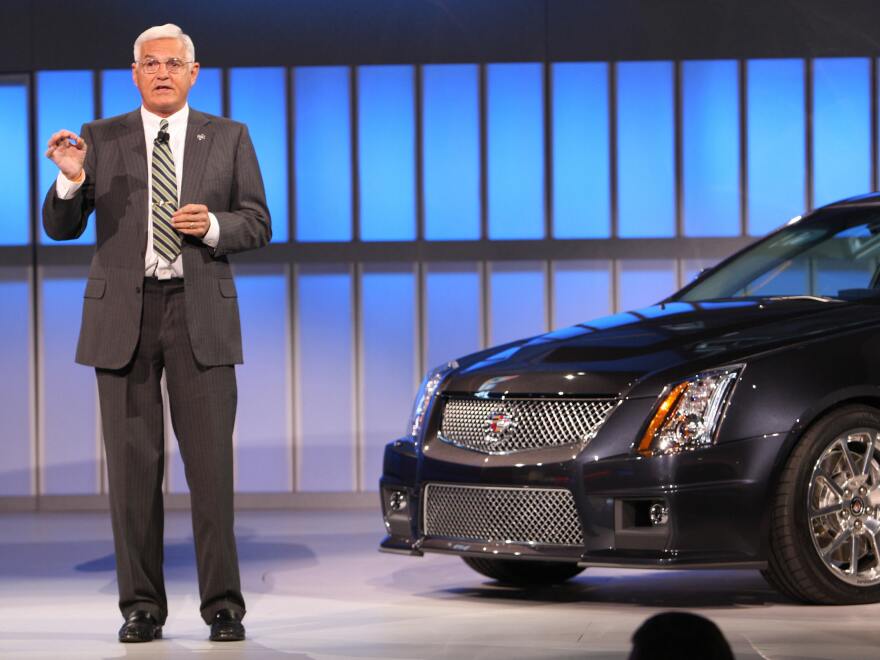

In 2001, when General Motors asked auto executive Robert Lutz to return as its vice chairman, the company wanted to limit what he did in his free time.

Like Bertolini, Lutz was an avid skier. Lutz also liked to ride motorcycles as well as race cars. He even owned and flew two military jets.

Lutz hasn't forgotten what he told the board.

"I'm happy to rejoin the company," he recalls. "But I need absolute freedom as far as my hobbies are concerned."

Eventually the board relented, and Lutz took the job. (Incidentally, he flew those planes until he was 87, when he failed an eye exam.)

"I encountered these restrictions my whole career," says Lutz, who also held senior-level jobs at Ford and Chrysler. But he adds that he "never took them very seriously, and got away with it for 47 years."

Corporate governance experts say founders of companies especially seem to enjoy a certain kind of impunity.

Bezos, for example, followed in the footsteps of Virgin Group founder Richard Branson, who made his own trip to the edge of space just days earlier.

And on the Fourth of July, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg posted a video on Instagram of him riding on a hydrofoil surfboard, holding an American flag, to John Denver's "Take Me Home, Country Roads."

Hillary Sale, a professor of law and management at Georgetown University, says there should be an open dialogue about an executive's hobbies.

"A good board talks about it, thinks about it, and prepares for it," she says.

When tragedy hits a company's leader

And there's good reason for that. Accidents do happen. It took a year for Micron Technology's stock to recover after its CEO, Steve Appleton, died piloting a small plane in 2012.

Yet boards are often unable to rein in their top executives' activities even if they are aware of the risks to companies.

"It's a bigger question whether a board can really say to somebody like their CEO, 'Absolutely not. You cannot do that'," according to Sale.

That's where executives and corporate governance experts say succession planning comes in.

These days, Bertolini is retired from Aetna, and he sits on a handful of boards.

He is on the other side of the table now, and Bertolini says that has given him a different perspective on the role an executive plays in the success of a company.

"You never want to be in a place where that person is indispensable to the success of the company," he says. "Nor do you want to, if publicly traded, to have a huge impact on market cap."

Bertolini says even as CEO he was mindful of the risks to the company his activities posed. At Aetna, he says, he discussed succession planning at every board meeting.

For executives, having that plan in place helps mitigates some of the risk to companies. And they believe that having daredevil CEOs is not a bad thing after all.

Lutz, for example, believes companies would be more successful with CEOs who like taking risk — "as opposed to, you know, calm, peaceful guys who never want to put themselves at risk, always drive the speed limit, and drive a minivan as their only vehicle."

"Who the heck wants a person like that to lead a corporation, or to be in a leadership position at a corporation?" he asks.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.